Laurel Canyon's Tequila Sunset

The canyon contemplates what it had been and what it was in fact becoming as the end of the '70s loomed. "Your ballroom days are over, baby," Jim Morrison had warned, "night is drawing near..."

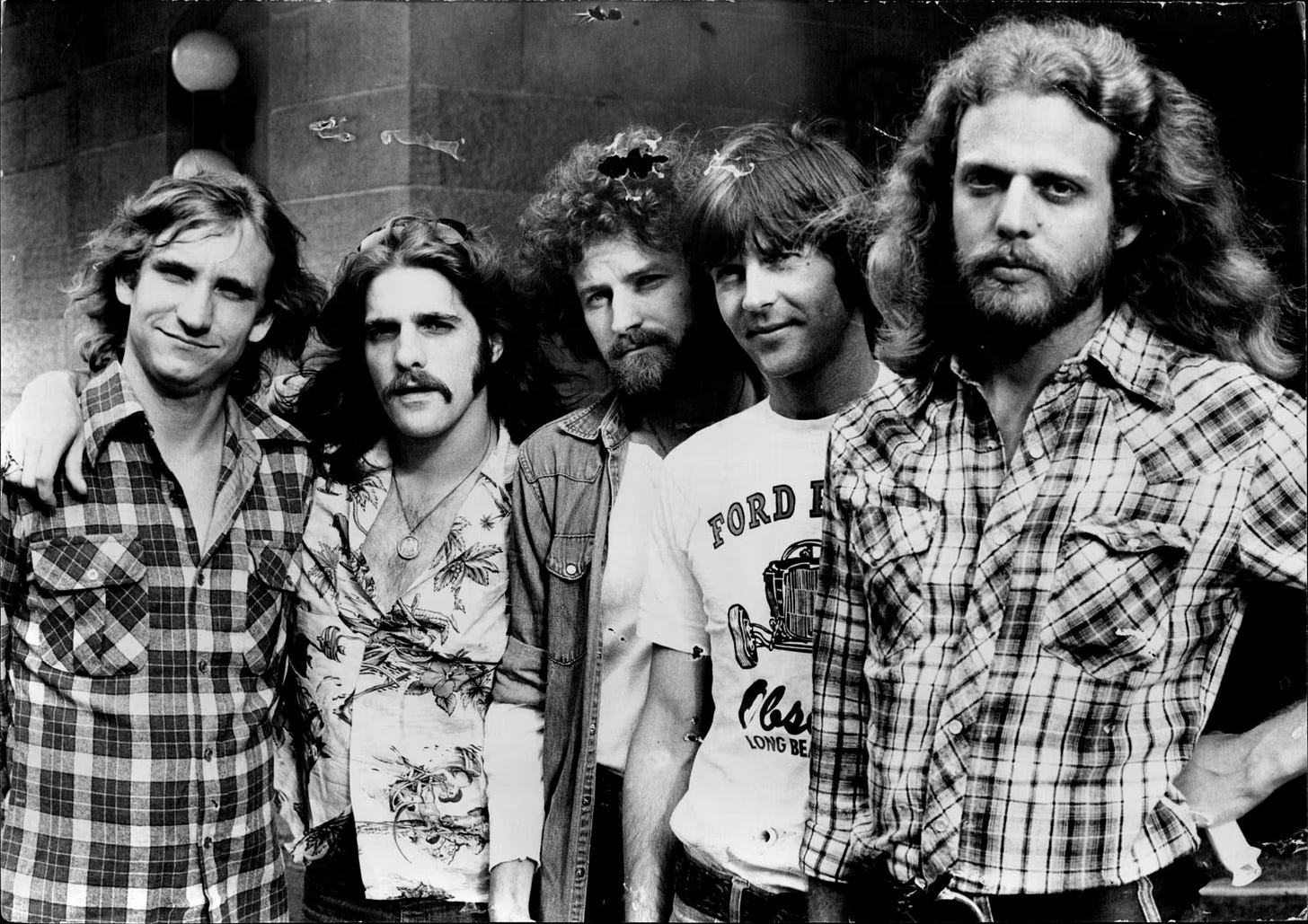

Just when L.A.’s singer-songwriters and country-rock cowpokes looked as if they had a lock on Sin City in the early ‘70s, Los Angeles and the canyon were rattled by one of those rude imports that England likes to lob at the former colonies to remind them the sun hasn’t entirely set on the empire. It had been roughly ten years since the British Invasion taught L.A.’s feckless folkies and surfin’ safarians how to be rock-and-roll stars; now the Brits meant to set the agenda again, this time with a superfabulous confection known as glam. Glam was rock and roll that raged with style and the slimmest soupçon of substance, the inevitable product of a rock-and-roll culture in England then suffering from a surfeit of drugs and boredom. Whereas the Eagles and Brownes and Mitchells and Kings were at that moment writing deadly earnest introspections about relationships or, in the case of the Eagles, the mythos of the American Southwest as seen from Sunset Boulevard and Laurel Canyon, English glam bands like the Sweet, T. Rex, Slade, Mott the Hoople, and Gary Glitter were singing about...well, it was hard to tell sometimes. T. Rex’s Marc Bolan, exemplar of glam, appended these lyrics to “Bang a Gong (Get It On),” the group’s signature song and, in America, its only real hit: “You’re an untamed youth / That’s the truth/With your cloak full of eagles / You’re dirty sweet and you’re my girl.”

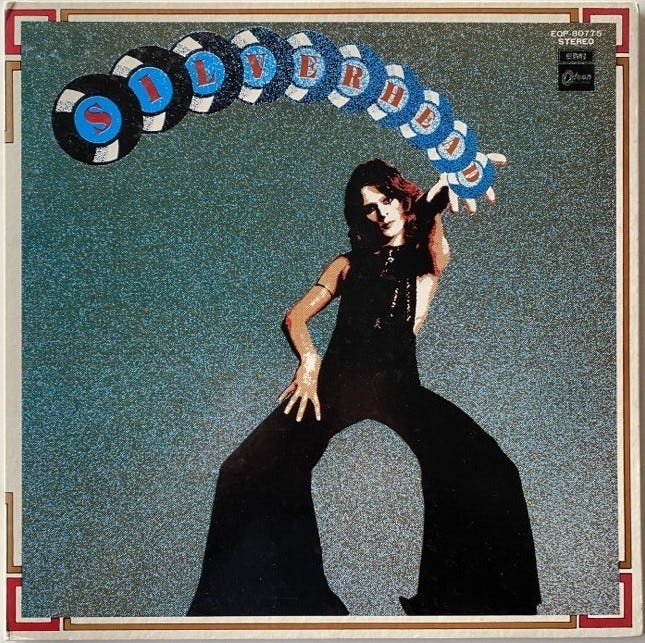

Glam performers gave off fuzzy sexual vibes—even though most were avowed heterosexuals—a bit of theater baffling to American rock and rollers and frightening to large swaths of the country. “I mean, nobody had seen anybody like us in Mobile, Alabama, in 1972,” Michael Des Barres, who moved to L.A. from London with his glam band, Silverhead, told me. “I’m in a yellow dress and blue cloche hat, and these rednecks want to fuck me or kill me, they didn’t know which.”

Glam per se was never as big in the United States as it was in Britain, where sexual ambiguity in pop-cultural icons was and remains far less threatening. But it had a profound effect on the New York and L.A. music scenes. Glam legitimized L.A.s Alice Cooper, whose dabbling in eye makeup and rock-as-theater heretofore had garnered only crumbs—by 1973 the band was selling out arenas with Alice appearing onstage in ripped leotards while the Trans Am-diving youth of Omaha and Indianapolis roared in full-throated approval. In New York City, Lou Reed, late of theVelvet Underground and Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, began appearing in mascara, bondage leathers, and chromium dog collars and soon had his first bona fide hit with “Walk on the Wild Side,” a roll call of the Max’s Kansas City back room. Then there was David Bowie, who had started as a sort of pansexual folksinger, emulating Dylan, but soon appeared in drag so extreme that it made Cooper and Reed look like Pittsburgh Steelers. He famously turned himself into a character/caricature, Ziggy Stardust, with his band the Spiders from Mars. Almost alone in the glam movement, Bowie had style and substance, as well as an unfailing sense of the moment. When he had wrung every last flake of glitter from glam, he hung up his platform boots and remade himself into an uptown R&B crooner just in time for disco.

Glam was a hit in New York—the outrageously femme New York Dolls would have been impossible without it—but it was an even bigger hit in L.A. Drugged-out rock and rollers flaunting six-inch platforms, roosterish haircuts, and feathered boas somehow seemed right at home in Hollywood, where glamour has always been smudged with decadence. Glam didn’t supplant L.A.’s singer-songwriters, who were then consolidating their market domination, or the established blues-rock giants like Led Zeppelin, but its gender-bending and celebration of the glib and glamorous were in some ways more in sync with the times than Linda Ronstadt. “A lot of it was just that, the superficiality of it,’ Des Barres told me, “and Silverhead was way more interested in the superficiality of rock and roll.”

America was at the moment in the throes of an energy crisis, a crippling recession, and Richard Nixon’s wrenching, slow-motion self-destruction. Bad times have historically encouraged the creation of irresistible cultural froth; glam provided the same escapism as Nick and Nora movies had during the Depression. Glam also brought to the mainstream camp attitudes previously the province of gay culture, and it had the palliative effect of rejuvenating rock and roll while prefiguring the truly revolutionary punk movement that would follow close on its heels.

Glam was a signal event in the lives of many musicians then growing up in L.A. A young misfit named Frank Ferrana, at the time being raised in transience at the Sunset Towers apartment building on the Strip, was obsessed with the Sweet’s vocalist, Brian Connolly, and why, among other matters, Connolly had “bangs that curled under.” Ferrana would soon change his name to Nikki Sixx and found Mötley Crüe, which at the dawn of the ‘80s led a brace of L.A. “hair” bands who took glam’s lace-and-mascara costumes and coiffure and wed them to meat-and-potatoes rock and roll, reviving the Sunset Strip after punk imploded and selling millions of records.

Glam was a signal event in the lives of many musicians then growing up in L.A.in the ‘70s. A young misfit named Frank Ferrana, at the time being raised in transience at the Sunset Towers apartment building on the Strip, was obsessed with the Sweet’s vocalist, Brian Connolly, and why, among other matters, Connolly had “bangs that curled under.” Ferrana would soon change his name to Nikki Sixx and found Mötley Crüe.

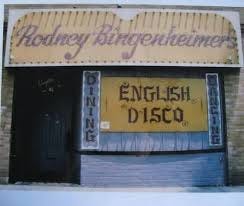

Ground zero for L.A. glam was Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco. A gnomish scenester from Mountain View, California, Bingenheimer had served as a genial aide-de-camp to Sonny and Cher and as Davy Jones’s stand-in on The Monkees before working for several L.A. record labels. He hauled the then-unknown Bowie around to L.A. radio stations in his pre-Ziggy days and, after sampling the glam scene in London with him, opened the English Disco at 7561 Sunset in 1972. (It was briefly located next to the Chateau Marmont.) For two years the tiny club vied with the Rainbow Bar and Grill as the main watering hole for British bands, glam or not, as well as for a delirious cross section of L.A.musicians and hangers-on—from Shaun Cassidy to Alice Cooper to Iggy Pop—along with neo-celebrities like Mackenzie Phillips, daughter of the Mamas and the Papas’ John Phillips, then in her wild-child phase. (Silverhead’s second album, 16 and Savaged, was inspired by the ferocious, extremely young groupie scene at the club.)

Glam would barely outlast Rodney’s, which closed in 1974. In the meantime, Laurel Canyon lost any semblance of being a latter-day Bloomsbury as the first wave of musicians moved out and the drug dealers moved in, even as the mystique from the Joni-CSN-Byrds collective played on in a sort of plaintive counter-point as the canyon, clotted with musicians, record producers, and dope dealers, began to morph into an altogether harder and more cynical place. “Laurel Canyon” was now fixed in pop-cultural amber along with “Haight-Ashbury”and “Woodstock” as one of the ciphers of the ‘60s; questioning the myth was, at this juncture, out of the question. Nevertheless, what the canyon had been and what it was in fact becoming were increasingly at odds. In the post-Manson, pre-punk days, sheer hedonism began to overtake the hippie ethos that had shaped the canyon since the mid-’60s. “Now I’ve drunk a lot of wine and I’m feel-ing fine,” Mott the Hoople’s Ian Hunter sneered in the Bowie-penned 1972 smash “All the Young Dudes,” which served as glam’s unofficial manifesto and, for many in the canyon, a lifestyle mission statement. The canyon in the ‘70s more closely resembled a Dionysian playground with no compensating world-view beyond having a really, really good time. And pulsing at all times behind the merriment was the exuberant rock and roll of the ‘70s.

Mark Belack (not his real name) lived in a cottage on Weepah Way, one of the precarious trails threading the Kirkwood Bowl. It is axiomatic that the canyon’s every byway must have storied residents past and present, and Weepah was no exception. Belack’s neighbors included Keith Carradline; John Paul Getty III; Patrick Reynolds, heir to the Reynolds tobacco fortune; and Susan Tyrrell, riding high on her best-supporting-actress Academy Award nomination for 1972’s Fat City. Belack worked at the radio station KHJ, but the cost of livng in the canyon was such that he and his roommate, a boyhood friend from Northridge, could afford to drive an Alfa Romeo Veloce Spider and a Porsche 911, respectively. “Our rent was nothing,” Belack told me. “Our landlady loved us, just loved us, so all of our money went into partying and nice clothes and nice cars.”

The house itseIf was modest but touched, like so many structures in the canyon, with infamy—Bill Eppridge, who took the iconographic photo of Robert Kennedy sprawled on the kitchen floor of the Ambassador Hotel, was the previous tenant. The house also had the block’s only swimming pool. “It was almost like a commune,” Belack recalled. “You couldn’t help not get to know just about everybody because it’s like living in a hallway. Your neighbor’s right there on your fence: ‘Can I come over and go swimming? Who’s at the Whisky? What passes did you get for tonight?’ This doesn’t happen in a suburban neighborhood. Laurel Canyon was special, it was rockin’, it was fun. It was like: step outside your door, there’s a party. Many of the people were in the music industry. Nobody had a job, like, at Macy’s. Everybody was interesting, everybody was a bit of an artist no matter what, a bit bohemian and unusual.” One afternoon, in a flash of LSD-induced inspiration, it was decided that flooding Weepah would be an amusing diversion. “I think I started it,” Belack told me. “I was washing my car.” Hoses were led to the steeply pitched street—a concrete drainage channel ran down the middle—followed by Belack, Reynolds, Tyrrell, and Getty careening downslope on inner tubes. How does it feel to be one of the beautiful people? John Lennon queried, in a different context, some years before. The answer was: It felt great. “There were actors, models, everybody was really good-looking,” Bellack recalled. ”I must say there weren’t any ugly people in Laurel Canyon. There really weren’t.”

A typical day for Belack during those summers began by ceremonially injecting a watermelon with vodka and dumping it in the pool so that it would cool by the time he and his roommate returned from work. (In winter, firewood was available from a cord in front of David Carradine’s house.” He was never there, ever, but there was always a fresh stack of firewood,” Belack says.”We’d fill our arms and go, ‘Thank you, Grasshopper.’”) The boys made ready for the night by first playing a favored musical selection. “We’d start off by listening to ‘Low Spark of High-Heeled Boys’ We primped as much as the girls.” The primary fashion accessory was platform shoes.” That cracks me up because everybody walked all over the canyon back then—the heels on those shoes were like that—and if you got all the way home and forgot to get cigarettes, you’d go, fuck it, and walk down to the Canyon Store in them.”

Soon the evening’s guests would arrive. “The girls would drive in from the Valley or Hollywood. All the girlfriends we had were total rockers: the leopard skin, the lipstick, the giant Rod Stewart hairdos. They were always dressed to the tens.” As for the attraction, “We were young, had a pool to sit around, and lived in Laurel Canyon. We were getting free passes to the clubs. And because the labels were sending the jocks at KHJ stacks and stacks of please-play-me records, promo things with a hole punched in them, we had albums that weren’t in the stores yet, so we could call the girls and say, ‘Guess what we’ve got?’”

After the obligatory joints and cocktails, the entourage adjourned to the Strip. “We’d all pile into one or two cars so we wouldn’t have as much hassle parking on Sunset.“ From there it was on to Rodney’s, whose proprietor, in a fit of generosity, had befriended Belack and his roommate, an endorsement that served to swell the ranks and toothsomeness of their lady friends. “Plus, we liked to dance, and not a lot of guys would, and all the girls wanted to dance. So we were really popular.” One night, preparatory to hitting the Rainbow’s tiny upstairs dance floor, Belack and his entourage rigged the soles of their platforms with gun caps to facilitate satisfying explosions—Chess King-clad flamencos on the Sunset Strip. “It was a big hit. Everybody started doing it. For a couple of months you couldn’t buy caps anywhere in town.”

In addition to the vodka-infused watermelon, the beer and sangria, the occasional tab of acid, there was cocaine. “A lot of cocaine,” Belack clarifies. “It was so available, and everybody had it. Everybody had a little spoon around their neck with the little spread wings, the angel of cocaine or whoever she was. Then of course everybody had the little amber vial with the black lid and a little chain on top so you could do a one-handed bump.” Demand having a way of outstripping supply, bulk coke purchases were favored.” First of all, you wouldn’t buy a gram. You’d buy an eight-ball. You’d go in on it with your friends.” In the rare event one couldn’t score,”you could always go to the Canyon Store and just stand in the parking lot for a while, say to somebody: ‘Hey, I’m looking for some blow, you know anybody?’ But nobody had to do that. It was just rampant; it was everywhere.” Still, ”this was Laurel Canyon. If we were out in Reseda it would be different. It was all about getting high and it was cool. Somehow, we all managed to keep our jobs.”

“Laurel Canyon was special, it was rockin’, it was fun. It was like: step outside your door, there’s a party. Many of the people were in the music industry. Nobody had a job, like, at Macy’s. Everybody was interesting, everybody was a bit of an artist no matter what, a bit bohemian and unusual.”

By the mid-’70s, the sheer surfeit served up by the record industry seemed as if it would never end. The hits just kept on coming for Laurel Canyon’s alumni. Carole King’s Tapestry kicked off the decade by rocketing to No. 1 and forging the template for the enormous L.A. singer-songwriter albums to follow. Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark, released in 1974, would become her most successful record, reaching No. 2. Jackson Browne racked up three gold albums in the ‘70s before hitting The Pretender out of the park in 1976. The same year the Eagles, with a fistful of Top 10 hits under their belt and despite losing founding member Bernie Leadon (replaced by Joe Walsh), released Hotel California, which stayed at No. 1 for eight weeks and produced two No. 1 hits. Troubadour sweetheart Linda Ronstadt hit No. 1 with 1974’s Heart Like a Wheel. Fleetwood Mac, a sputtering former British blues band, added the L.A.-based duo Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks; reconstituted with a sleek L.A. sound, sold 4.5 million copies of 1975’s Fleetwood Mac before unleashing 1977’s Rumors, which sold was No.1 for seven months and sold 19 million copies. These were numbers unimaginable even by Beatles standards, and they utterly changed the record industry, reshaping the priority of the labels and the expectations for the talent—and, inevitably, the tenor of life in the canyon.

Michael Des Barres was at that moment coming to grips with daily life in the canyon as a nominal rock star in residence. “In ‘72 I hadn’t had time to get fucked-up and paranoid. It was all joyous, it was great: I’m twenty years old and I can stay up for a week. There’s a problem?” By the time he had settled in the canyon, he was less sanguine. “Then the reality sets in. What it really was, was seedy. And wood. Lots and lots of wood. I’m not a big wood fan. I like metal and concrete and stuff.It became: Go to Ralphs”-the ubiquitous Southern California supermarket, whose Hollywood location on Sunset was known, then as now and probably forever, as the Rock and Roll Ralphs—and go shopping. Then I’m not in my yellow dress and blue cloche hat and platform character shoes. The practicalities of it were something else.”

Des Barres’s glam band, Silverhead, had dissolved after two albums. By 1977 he was lead singer of Detective, a band put together under the auspices of Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song vanity label. A Zeppelin clone launched into the gathering punk explosion, the band never stood a chance, and Des Barres knew it. “I did it because of [Zeppelin manager] Peter Grant and Jimmy [Page] and because of a very interesting concept: a green card. I needed that fucking green card, and needed the money. [Detective] was a corporate band; this wasn’t young kids coming together in the garage. I called it my green card band.”

In 1978 the Sex Pistols played their first and only American tour. Des Barres was in the audience at what turned out to be their last gig, in San Francisco. “I was in this cruddy thunking metal band and I went up and saw them. The experience was shattering. Des Barres, no stranger to onstage charisma,was astounded by the Pistols’ singer, Johnny Rotten (né Lydon). “For me, he’s the Bob Dylan of that era. It was a combination of his utter confidence, the certainty that what he was doing was completely new and completely himself. ‘This is me, take it or leave it. I could give a fuck what you think.’” The audience in San Francisco, Des Barres recalled, “was in silence, unbelievably mesmerized, and Rotten just looking at them. The last thing he ever said onstage was,’You ever feel you’ve been cheated?’ And meanwhile, Sid”—Sid Vicious, the band’s bassist—”is on his knees picking up the money they’ve thrown. Then, blackout, and they were gone.”

As the ‘70s waned, there was a palpable sense in the canyon and across L.A. that the lush vistas that started the decade were being squeezed as if by the iris of a camera lens closing.

The concert was a watershed for Des Barres. ”The rock-and-roll gods would dictate that I would see John Lydon in all his Clockwork Orange brilliance,” ticking off the Pistols’ signature broadsides at the corpulent ruling class in England and, by extension, the ruling class of rock and roll as represented by bands like Led Zeppelin and the canyon’s singer-songwriter elite. “‘Anarchy in the U.K.’ ‘God Save the Queen’—it so needed to be said, it really did, and he said it. I was singing about ‘I want to fuck you, baby, let’s have a party.’” Three years after glam peaked, the Pistols had served notice that the party—and a lot else—was over. Detective released two albums, both of them plodding failures, and was scheduled to begin recording another. After seeing the Pistols perform, Des Barres knew that it was pointless. “I was meant to go back to rehearsals with Detective for the third record, and I said, ‘Fuck it, I can’t do it.’”

As the ‘70s waned, there was a palpable sense in the canyon and across L.A. that the lush vistas that started the decade were being squeezed as if by the iris of a camera lens closing. “You’re ballroom days are over, baby,” Jim Morrison had warned, presciently, a decade earlier, in the Doors’ “Five to One,” “night is drawing near…” Bill Graham had long since shuttered his Fillmore theaters. His San Francisco rock palace Winterland where the Sex Pistols would later play their final gig—was used by the Band in 1976 as the venue for a farewell concert filmed by Martin Scorsese, The Last Waltz, which included performances by a who’s who of guest stars that included Joni Mitchel, now in her thirties and performing free-ranging jazz excursions that bore little resemblance to her dulcimer-strumming Lookout Mountain repertoire. (Graham finally closed Winterland following a final concert featuring the Grateful Dead on New Year’s Eve,1978.)

If punk had punctured the mystique of bloated rock stars in the late ‘70s, disco dealt a mortal blow to the canyon country rockers. Whereas punk sold sporadically in the United States, disco was racking up numbers that sometimes eclipsed even the biggest L.A. singer-songwriters. The soundtrack to Saturday Night Fever sold thirty million copies worldwide. Casablanca Records, home of disco queen Donna Summer, briefly became L.A.’s hottest label. Its chaotic Arabian Nights-themed headquarters on the Strip sported a parking lot full of Mercedes-Benz convertibles, mirrored executive suites, and throbbing disco punctuated by the sound of staffers hoovering hectares of cocaine. “When disco came in, that was the end of it,” Sally Stevens, then working at RCA Records, weak sister of the major label, to me. “You can’t dance to country rock.”

Casablanca Records, home of disco queen Donna Summer, briefly became L.A.’s hottest label. Its chaotic Arabian Nights-themed headquarters on the Strip sported a parking lot full of Mercedes-Benz convertibles, mirrored executive suites, and throbbing disco punctuated by the sound of staffers hoovering hectares of cocaine.

One morning in 1979 Stevens walked into her office and beheld a young man she didn’t know standing there. “He said, ‘Hi, my name is Vince Gill and I was told to come see you.’” Gill was the lead singer of Pure Prairie League, a country-rock band that had scored a hit, “Amie,” in 1975. RCA was slashing its roster, and Pure Prairie League was among the bands to be let go. Stevens had been delegated to give Gill the bad news, which she ascertained only after excusing herself and buttonholing her superiors. “So I had to go in and say to Vince: ‘Gee, I’m awfully sorry. I really apologize. This is a horrible way to treat you. I don’t know who you are, and you don’t know who I am, and that should give you a good idea of what you’ve walked into. But the bottom line is they’re not going to support Pure Prairie League. Country rock is over.’” Stevens then told the stunned young musician, with remarkable prescience, what the future held. “‘Right now they want disco; they don’t want this stuff anymore. And I’m sure ten years from now you’ll have the last laugh on this label.’ And he said, ‘Thank you very much for being honest.’ I said, ‘I’m sure I’m not far behind you, and that turned out to be the truth because they laid all of us off.”’ It didn’t take long for Gill to have the last laugh. Within the year, the bottom fell out of disco and took the record business with it. PolyGram Records, corporate parent of Casablanca, didn’t return to profitability until 1985. Gill reemerged in the ‘90s as a gigantic country-music star with a string of Top 10 hits and multiplatinum albums.

As disco pumped up and then decimated the record labels, punk was still tearing its way through the L.A. scene. On and off the Strip, the clubs that had catered to the Byrds and the Doors and then to glam were booking soon-to-become Los Angeles punk legends X and the Germs. Outside the Whisky, where flower children formerly gathered in at least a pretext of peaceful good vibes, the sidewalks were clotted with loutish, self-dramatizing punks. ”They would just stand there in front of cars or fall across the hood and stare at the people inside,” L.A. photographer David Strick told me. ”You’d see the beginnings of this kind of free-floating hooliganism.” The punk shows were becoming dangerously vi-olent. Derf Scratch, bassist in Fear—John Belushi’s favorite band during his final, sodden days in L.A.—was badly beaten after the band came offstage one night.

Record Plant co-founder Gary Kellgren drowned in his swimming pool in 1977. “It was this sense of one of those typical Brian Jones endings to one of these ‘60s people in the ‘70s when his string got played out in that scene.”

Strick, on a magazine assignment in 1977, spent a night at the mansion of Gary Kellgren, a prominent recording engineer and producer who’d co-founded the Record Plant studios in New York and L.A. “The reason the magazine was doing a story on him was because he’d become sort of a casualty of the scene, even though he had a ton of money. He’d become just completely dissolute and fucked up.” Strick hung around Kellgren’s faux-Norman castle above the Strip for a single night. “He had this sicko entourage that just kind of came by and brought him drugs. All kinds of music-fringy people.He was still working—he took us to a Frank Zappa session at the Record Plant that he was supervising at five in the morning. Around midnight a couple of long-haired Samoan guys came to the castle and dropped off a pretty large amount of cocaine, which as I remember was wrapped in condoms, because Gary Kellgren put one through his belt loop for the rest of the night.”

Months later, when Strick’s photos were about to run, he got a call from the New York Post. Kellgren had been found floating dead in his swimming pool and the newspaper wanted Strick’s pictures. He was 37. “It was this sense of one of those typical Brian Jones endings to one of these ‘60s people’s lives in the ‘70s when his string got played out in that scene.”

Meanwhile, the compleat L.A. cocaine cowboys were having second thoughts. The peaceful, easy feelings of the Eagles’ first records grew progressively darker as the decade wore on, culminating in the Hotel California’s unsparing allegories about the soul-sucking wages of L.A. in the seventies even as the album went to No. 1 and sold more than six million copies its first year of release. Said the band’s co-founder and chief lyricist Don Henley: “Those kinds of record sales were unprecedented. I guess everybody thought it was going to continue like that. Lots of money was spent on parties and champagne and limos and drugs. And then of course the bottom dropped out…I think we intuitively that it would pass. I think we could sense the future. I mean, this was the dream we all had. This is why we came to California. It just got bigger than we ever expected it to. It kind of scared us, I guess.”

Brilliant capture of that cultural inflection point. The Gary Kellgren portrait - becoming "completely dissolute" even while still producing at the Record Plant - perfectly crystallizes the canyon's late 70s paradox. Still functioning professionally but spiritually hollowed out. Saw something similar hapenin tech booms where success metrics keep climbing while the underlying culture corrodes.

Fabulous writing about my hometown and glam to punk! I am on the last chapter of the book BTW, I am a slow reader these days but I absolutely love your writing Michael. I saw Michael Des Barres in the 80's at the Roxy. My girlfriend and I decided we would dress glam and in the bathroom Pamela DesBarres and Melanie Griffiths approved our gear as we said we wanted to be groupies like the GTOS. Off we went to the front of the stage and Michael stops mid song points at me and says "I love your boa." That was a defining moment for our short lived groupie stage. I missed out on Rodneys English Disco. I was a few years too young but I wanted to be just like those girls Lori and Sable and Pamela hanging out with the rock stars. Then there were The Runaways, that was amazing...Cherie and Joan Jett in platform boots! L.A. was amazing. I got in on the punk scene in clubs in the valley Godzillas and Perkins Palace in Pasadena. Then the whole new wave/power pop scene and all the great bands coming from the UK playing the Hollywood Palladium. Music was cool all the way through the brit pop shoegaze scene when all those Creation Records bands were touring the States...playing at the Whiskey, Roxy etc. To me Disco didn't kill it, rap/hip hop did.