The Managers: Peter Grant, Led Zeppelin

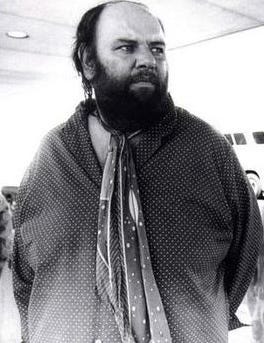

Zeppelin's fearsome leader was "a gypsy king in the forest of rock and roll, sitting at the end of a table laden with eggs Benedict and cocaine."

It occurred to me while reporting What You Want Is in the Limo that the men who managed rock and roll in the fifties for the most part had no affinity for the music or musicians they represented beyond the cash they generated. Colonel Tom Parker, a carny sharp and convicted con who immigrated illegally to America from Holland, outflanked several more plausible managers and seized complete control of Elvis Presley's career in 1956. Shrewd enough to grasp the potential of a white singer making “race records" palatable to the vast white teenage American audience of the 1950s, shameless enough to keep his boy Elvis from lucrative European performances for fear of his own deportation, Parker tended to Elvis's interests with single-minded zeal. Twice Presley's age, the Colonel controlled every aspect of the King's life and career, aggressively licensed his name and likeness no matter how cheap or vulgar the product, steered him into appalling movies, and eventually claimed up to 50 percent of his income.

Rock's second coming in the mid-sixties introduced several new flavors of manager, few particularly savory. Given that British Invasion bands and their hits were driving the business, British managers were suddenly thrust into shepherding the careers of their charges not only in Britain but in America, where some were hopelessly out of their depth. Brian Epstein, the Beatles' manager, was punctilious, polite, and thorough; he looked after "the lads" with paternal care and reshaped their image from leather-jacketed rough boys into the besuited Fab Four who ended their historic performance on The Ed Sullivan Show with meticulous bows.

But Epstein was a fatally inexperienced show businessman and so badly underestimated the group's merchandising potential—the street-wise Colonel Parker cashiered $20 million worth on Elvis’s behalf in 1956 alone—that he signed away a breathtaking 90 percent share of merchandising income in the U.S. to a third-party outfit named Seltaeb (Beatles spelled backward). Though Epstein renegotiated a still embarrassing 49 percent cut when he realized his mistake, in the litigation that followed, American chain stores canceled their merchandising contracts. The fiasco ultimately cost the Beatles an estimated $100 million. As Paul McCartney later lamented, Epstein “looked to his dad for business advice, and his dad really knew how to run a furniture store in Liverpool."

As the sixties progressed, an altogether different breed of manager asserted itself in Britain. The most notorious was Don Arden (father of Ozzie Osbourne’s future wife, Sharon), a former tummler who combined Colonel Parker's opportunism with a ruthlessness that earned him the sobriquet "the Al Capone of Pop." As recounted in Starmakers and Svengalis, a history of British rock management by Johnny Rogan, Arden's break came via Jimi Hendrix's future co-manager, Michael Jeffery, which Arden parlayed into managing the Nashville Teens, cresting on their hit version of John D. Loudermilk's “Tobacco Road."

Peter Grant single-handedly rewrote the rules of engagement that promoters had to follow when dealing with Zeppelin, which were quickly adopted by grateful fellow managers and became industry standards. Substantial income that would have gone to middlemen now flowed directly into the band’s accounts, enabling Grant to purchase a country estate accessible by a drawbridge spanning a moat rumored to be stocked with alligators.

Arden kept the band on the road, where they earned decent money but seldom saw much of it. When the Teens' pianist, John Hawken, demanded to be paid in full, Arden lifted him by the throat, pinned him against a wall, and bellowed,"I have the strength of ten men in these hands!" then dragged the terrified pianist to an open second-story window. Hawken managed to flee before finding out whether Arden was bluffing. Perhaps not. Having added the Small Faces to his stable, Arden discovered that an associate of Robert Stigwood, later to manage Eric Clapton, had made overtures to the group. According to Rogan, Arden and four intimidating wingmen descended on Stigwood's London office, where Arden dangled Stigwood by his legs four stories above the street. Stigwood's company never signed the Small Faces.

To cover his sprawling bookings, Arden employed an outsize former bouncer as his point man and enforcer. His name was Peter Grant, the same Peter Grant who, under the aegis of Led Zeppelin, would soon usurp from Arden the mantle of Her Majesty's Scariest Rock Manager. From Arden, Grant learned that absolute control and trust were essential when large sums of cash were involved, as well as projecting an intimi-dating facade that left no question that, as Arden informed a rival, “suicide might be better than causing trouble for me."

Michael Des Barres, future glam star and Zeppelin confidant, had no illusions about the provenance of the rock business he saw as a young Londoner. “The British gangsterism of the late fifties and early sixties informed rock and roll to a degree most people are unaware of,” he told me."The rhyming slang that was invented by criminals in the working class in London—to 'suss' somebody out—became the adopted language of rock and roll." Arden taught Grant the extremes that a manager must imply he is willing to invoke in the rock and roll wilderness, where a handshake and a menacing demeanor have the force of signed contracts. "They say there's honor among thieves," Cy Langston, the Who's early road manager, told me. “Don't get me wrong. But you get the vibe that what's said is said. It's a done deal.”

Grant was a natural antiauthoritarian, and his genius lay in challenging hoary show business norms that Led Zeppelin would soon render obsolete. He single-handedly rewrote the rules of engagement that record companies and promoters had to follow when dealing with Zeppelin, which were quickly adopted by grateful fellow managers and became industry standards. In exchange for co-financing, with Jimmy Page, the recording of Zeppelin’s first album, Grant secured not only total artistic control for Page but an upper hand in future business affairs with the Atlantic Records, the band’s label. As Zeppelin became a top concert draw, Grant slashed promoters' percentages from 40 percent to 10 percent on the premise that no "promotion" was required beyond announcing the concerts and watching them instantly sell out. Substantial income that would have gone to middlemen now flowed directly into the band’s accounts, enabling Grant to purchase a sprawling country estate accessible by a drawbridge spanning a moat rumored to he stocked with alligators.

Grant's roughneck background was suited to the nascent rock business of the mid-sixties, where men with little formal education—Grant left school at thirteen—but quick wits and a nose for cash carried the day. He worked a variety of odd jobs—stagehand, waiter, Fleet Street runner and as a professional wrestler and movie double for Robert Morley. Having tasted show business, Grant bought two minivans and hired out as a driver for early rock and roll acts and later road-managed Little Richard, the Everly Brothers, and Chuck Berry on their first tours of Britain. Eager to seize the opportunities presented by the wide-open rock and roll business, Grant established a management company with Mickie Most, the Yardbirds' producer, and struck pay dirt with the New Vaudeville Band, whose novelty song "Winchester Cathedral" hit number one in the U.S. in 1966.

When the band was about to leave for an American tour, they recommended that Grant hire as roadie one Richard Cole. It is here that, as in a movie, the opening riff to "Whole Lotta Love" should fade up ominously, for the meeting of Grant and Cole—former boxer, scaffolder, and budding rock buccaneer—would have lasting consequences for the business of touring rock and roll. Other bands of the early seventies had sold-out tours, but few earned as much as Zeppelin, nor traveled amid an entourage as aggressive, paranoid, and ganglike."The common denominator in the operation that Peter Grant and Richard Cole ran was fear," Danny Markus, an executive at Atlantic Records, who traveled extensively with the band, told me. “They were thugs, and they ran it like thugs." But all of that lay in the future; Grant appraised the specimen demanding thirty pounds a week to road manage the ludicrous New Vaudeville Band and hired him on the spot.

"The common denominator in the operation that Peter Grant ran was fear" Danny Markus, an executive at Atlantic Records, told me. “They were thugs, and they ran it like thugs."

In 1967, Grant took over the faltering Yardbirds from their latest manager, Simon Napier-Bell. By then Jeff Beck had departed the group—soon to release his first solo album—and Jimmy Page was struggling to keep the band together, though by then, flayed by endless tours, incompetent management, and no real money despite their fame, they were exhausted and apathetic. When Grant took them on, he and Page formed an immediate if unlikely bond: the giant, uncouth former wrestler simmering with resentment and potential violence, and the wan, weedy guitarist genius who abandoned touring for session work after contracting mononucleosis from the stress of the road. It is the beginning of a relationship that will sustain and enrich both men for the next thirteen years. "Jimmy loved Peter and Peter loved Jimmy,” Des Barres told me."They were absolutely loyal and faithful to one another, like Elvis and the Colonel.”

With Grant in charge, the Yardbirds were booked for what would become their final tour of America, in 1968. With Beck gone and Keith Relf, never a strong leader, retrogressing as front man, the power in the Yardbirds shifted entirely to Page, who divined in the tatters of the band the outlines of Led Zeppelin. Even then, the Yardbirds performed a version of what would become "Dazed and Confused,"the spooky dirge and highlight of the first Led Zeppelin album, lifted uncredited from a song by the New York folksinger Jake Holmes (presaging Zeppelin's attribution troubles with "Whole Lotta Love,” among others). The Yardbirds broke up for good when the band returned to Britain. In the aftermath, Grant secured for Page the rights to the Yardbirds name; and Page set about recruiting what was first billed as the New Yardbirds but what was, once John Paul Jones, Robert Plant, and John Bonham signed on, Led Zeppelin in all but name.

Having in America had a firsthand look at the vast potential for the right kind of rock band, Grant waited as Page put one together. Despite his profane, preemptive style, Grant meddled not at all in the creative side, trusting Page and his handpicked bandmates to take care of the music; Page and the band implicitly trusted Grant's business instincts. It was a mark of maturity and confidence on both sides that served them tremendously at a time when drug-fueled egos ruined the prospects of many promising bands. Grant already had a reputation for laying down his life for his charges; that he did so when none of them earned him any serious money was a credit to his character. With Led Zeppelin, he finally had musicians in his wheelhouse whose talent was commensurate with his instincts for taking care of business. As Grant soon made abundantly clear, he did not stand on ceremony or honor business as usual if it remotely contradicted Zeppelin's agenda. “Peter Grant cared solely about his artists," recalled music executive Danny Goldberg, who served as Zeppelin’s publicist on their 1973 U.S. tour. "Everyone else could fuck themselves."

Neal Preston, a Los Angeles photographer, would shoot the band in 1973 and thereafter tour with them extensively as their court photographer."They had a very, very, very small inner circle," Preston told me. “You look at the Stones—the Stones must have had easily ten times the staff that Led Zeppelin had. They were very careful about who they trusted. Peter was very of the street—he came from that rough, British hooligan background. He was very representative of that era of manager and that style of doing business." Grant told a friend of Preston's that “his nose could tell if someone was good people or not.'The nose does not lie' Peter, for whatever reason, trusted me and decided to welcome me with open arms into the fold." Danny Markus also made the cut, thanks to his capacity to absorb the band's abuse while doing their bidding. “I never let them see me sweat," Markus told me. “Somehow I got over the wall. There were so many perimeters, you didn't get inside. Nobody did."'

In addition to satisfying Grant's perfectionist work ethic, Preston told me,"there were other considerations and questions. Which were: 'Do you know how to keep your mouth shut?' ‘Is your ego bigger than any of the members of the band?' 'Do you want to be treated like the fifth member of Led Zeppelin?' The answers are obvious, but those were the litmus test that you absolutely had to pass." Grant would make sure that Markus was never entirely secure in his position. “I'm sort of like in on a pass: I don't play any instruments. I'm not in charge of royalties. I'm just here to help him get through this experience in America. He just had a way about pulling the rug out from under you and making you sort of fearful. He never, ever showed his wrath to me. But he was scary; he was very scary looking. I mean, he was like six five and weighed three hundred pounds and he wore these gigantic Hawaiian shirts and Navajo jewelry, and he loped when he walked."

“Peter Grant cared solely about his artists," recalled music executive Danny Goldberg, who served as Zeppelin’s publicist on their 1973 U.S. tour. "Everyone else could fuck themselves."

Marsa Hightower, a publicist colleague of Danny Goldberg's at the PR firm Solters & Roskin, becomes friendly with Grant while working the second half of Zeppelin's '73 tour. “If you were in the inner circle you were treated quite well. If not, you were fair game for abasement—no respect for those lovely little ladies, fawning photographers, or record company execs." Burned into Hightower's memory is the fate of the Los Angeles photographer Richard Creamer, "a paparazzo to be sure but a gentle soul and childlike in demeanor." Hoping to make entry into the Zeppelin fold, he enlarges and frames one of his photos of the band and brings it to the Riot House—neé the Continental Hyatt House, Zeppelin's notorious base camp on the Sunset Strip—“no doubt dreaming of making a connection and getting some appreciation from the bad boys of rock," Hightower told me. Instead, Bonham sits Creamer down and, as in a Tex Avery cartoon, smashes the photo down over Creamer's head, leaving the frame dangling around his neck.

If life is rough around Grant within the cloistered circle, it is memorably so outside the perimeter. Pat O'Day co-founded Concerts West, one of the first national promoters of rock concerts and thus instrumental in Grant's plan to circumvent local promoters and their fees; starting in 1973, Grant partners with Concerts West for the band's North American tours. O'Day witnesses Grant's singular style of roadwork and is both impressed and appalled. “Peter's intentions were to be protective, efficient, cautious and professional in all matters concerning the group,"O'Day recalled. “Unfortunately, he had a cocaine habit of proportions bigger than his own, and it left him argumentative, volatile and dangerous. Thirty days on the road with Led Zeppelin was like one year with any other group due to the tension.”

There is one man in rock and roll at the time who can see and raise Grant for sheer hardscrabble backstory and chutzpah. Bill Graham (né Grajonca), founder of the Fillmore concert halls in New York and San Francisco, was spirited out of Germany ahead of the Nazis as a boy and studied Method acting in New York before turning himself into a rock and roll dance promoter in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury. It was at Graham's Fillmore West that Led Zeppelin had their breakthrough performance on their crucial first U.S. tour in 1968. From the start, Grant and Graham seemed destined for some sort epic clash of ego.

“What I didn't like about Led Zeppelin was that they came with force,” Graham wrote in his memoir. “I didn't care for their image and what came back toward the stage while Led Zeppelin was playing: pushing, shoving, stumbling over one another with complete disregard for personal safety. Naked aggression." The feeling was mutual. The animosity between the camps, which Plant later characterized as "egos and territories and pecking orders,” would eventually boil over during a concert at the Oakland Coliseum in which Grant beat one of Graham’s employees so badly he ended up in the hospital and criminal charges were filed. But for now, however much he disapproves of Grant and his methods, Graham is happy to collect the 10 percent of Led Zeppelin that would otherwise go to a competitor.

Elsewhere, Grant took care of business in his inimitable fashion. On the eve of Zeppelin’s Madison Square Garden concerts in 1973, Grant is in fine form backstage at the Baltimore Civic Center, upbraiding the building manager after he discovers that unauthorized photographs of the band are being sold in the arena. “How much of a kickback are you getting?” Grant demands, massive as always, the turquoise outcroppings on his rings menacing. Robert Plant’s wails are heard faintly through the concrete-block walls in the dismal “dressing room,” the chafinng dishes arrayed amid sinks and urinals, as Grant relentlessly hectors the man. The scene is captured by director Joe Massot in one of the more compelling moments in The Song Remains the Same, the film Grant commissions to chronicle the ‘73 Zeppelin U.S. tour. (Some patient soul later calculates that Grant says fuck and cunt a combined eighteen times during the exchange.) Even allowing for the opportunity to preen, Grant’s tirade over what is probably at most a five-hundred-dollar loss to Zeppelin’s income stream seems completely in character; one can only imagine how he would have handled the matter had Massot’s camera not been turning. Grant’s nose for cash fails him only once during the tour, and spectacularly so: three nights later, before Zeppelin plays their final show, $180,000 is stolen from a safe at the band’s hotel. Richard Cole, who discovers the theft, is initially suspected but cleared. The crime is never solved.

Zeppelin's reputation had preceded them in America from 1968 onward. But as Des Barres told me,"When you get to the mythic reputation of bands, it's usually the people that are around them that create the myth and mythology. The artists themselves are so isolated that their myths are created for them by the sycophants whiling away their hours in the outer sanctum—Richard Cole and a couple other guys who worked for Peter on those notorious tours, who had sprung from the loins of gangsterism in the East End of London." Grant, on the other hand, was capable of generating mythology entirely his own.

“Peter Grant was like a gypsy king in the forest of rock and roll,” Des Barres said. “He sat at the end of a banquet table that was laden with eggs Benedict and cocaine. He wore jewelry around his neck that weighed more than I did. He was a massive man. In every respect.”

Thanks for reading (and loving!) What You Want Is in the Limo. And yes, the Zeppelin entourage was an island that by the time heroin was a major factor with some members was fiercely defended from outsiders. Will check out the Mark Blake book, don't think that was available when I wrote mine but would love to read, such a complicated and pivotal character in rock; have a great Saturday evening!

It really is a unique little island in the world of rock. I never got to meet Peter Grant, but I did hang out with (tour manager) Richard Cole in the '80s when he was living in L.A. I read "What You Want is in the Limo" (and loved it), and "Bring It On Home," the authorized (and meticulously researched) biography of Peter Grant by Mark Blake. Sharon Osbourne's autobiography, "Extreme," also goes into detail about the management practices back in the '60s. It certainly is a lost era!