Why the Right Ears Matter

Alice Cooper were on their way to oblivion in 1970. Then a neophyte producer named Bob Ezrin thought he heard a diamond in the rough amid their unrecorded repertoire.

Bob Ezrin was a nineteen-year-old classically trained musician and folksinger working for Nimbus Nine, a Toronto company headed by Jack Richardson, the producer of the Guess Who’s biggest hits, when he first encountered Alice Cooper. Manager Shep Gordon sent Easy Action, the band’s failed second album recorded for Frank Zappa’s side-hustle label, to Nimbus Nine, where the staff played it to gales of laughter and derision. “We didn’t know if Alice Cooper was a guy or a chick and eventually it became a standing joke around the office that if anyone messed up that week, he’d be forced to go and work with Alice Cooper,” Ezrin recalled. Ezrin had no idea that Gordon had deliberately targeted Richardson for reasons both whimsical and calculated. “What would be the most vaudevillian, pop-art, bizarre thing for an Alice Cooper record than for it to sound like a Guess Who record?” Gordon told me. “It just seemed it was very Alice Cooper to get the most commercial guy with the least commercial band.”

Despite Gordon’s entreaties—trying to force a meeting, he and the band traveled to Toronto and bivouacked in the Nimbus Nine reception area—Richardson was unmoved and dispatched Ezrin to get rid of the band. “Here’s this guy Alice Cooper,” Ezrin recalled. “His hair is stringy and down to his shoulders, his pants are so tight I can actually see his penis through the crotch. He’s talking with a slight lisp . . . I just could not handle it.” Ezrin passed, only to be dragooned to see the band perform at Max’s Kansas City in New York where he had an epiphany that they could become stars. Backstage, Ezrin told them, “I think you guys can make hit records.” The band, close to fainting with gratitude, summoned all of their punk bravura and responded, “That’s good—we think you can, too.”

Ezrin convinced a dubious Richardson to let him record the band even though Ezrin had no experience producing records. Warner Bros. reluctantly agreed to fund the recording of four songs. Unless the sessions strongly hinted at a hit single, the label made it clear it wouldn’t offer the band a contract. Alice Cooper were by then more than $100,000 in debt and barely subsisting in a farmhouse outside Pontiac, Michigan. In December 1970 they gathered with Ezrin at RCA studios in Chicago and spent the next six weeks playing as if their lives depended on it. Ezrin was far more at sea than he let on. “I leapt into it without any knowledge of how to do it—I learned on Warner Bros.’ dime.” When the band played him the songs they proposed to record, he wanted to vomit. As a musician himself Ezrin knew “what a really great song [felt] like— I had played a lot of them.” Amid the wreckage of the demos he thought he heard one—its chorus sounded to Ezrin like “I’m edgy,” except what Alice actually snarled was “I’m eighteen.”

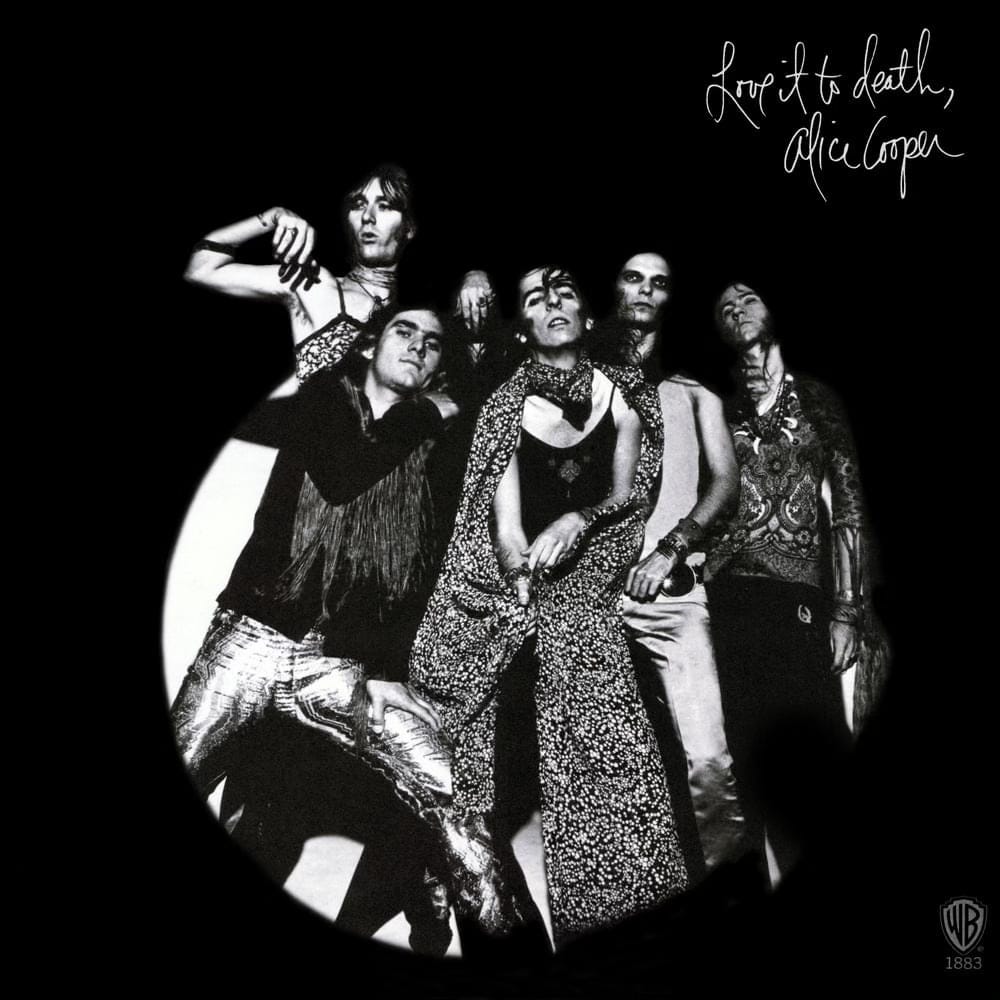

In the band’s original arrangement, the song lasted eight meandering minutes; after Ezrin was finished, it clocked in at two minutes and thirty-eight seconds. “I knew it would be a hit from then on,” he said. Warner Bros., at first refusing to believe the group was the same Alice Cooper, the improvement was so vast, released “I’m Eighteen” as a single. After the song hit number twenty-one on the U.S. charts, the label green-lighted Love It to Death, the album that drove a dagger through Alice Cooper’s swishy image for good and became their first gold record.

As Ezrin later told music industry columnist Bob Lefsetz:

First of all they had material that was already written—lucky me, it was at a moment where they’d had two albums to sort of find their way and had started to write actual songs. “I’m Eighteen,” for me, that was the beginning of everything, that was the first song we worked on. Listening to them play, they’d lose me for three minutes in the middle of the song and then they’d come back and it wasn’t the same as the beginning and everybody was playing lead all the time.

So my job was to find the essence of the song. There’s a great riff at the the center of an Alice Cooper song, whether it’s “School’s Out” or “I’m Eighteen.” And so where’s that, and what are we singing about? I was too stupid to know that words didn’t matter. I thought they did and it turned out I was right.”

Two years and three Ezrin-produced albums later, Alice Cooper hit Number 1 in 1973 with Billion Dollar Babies. Ezrin would go on to produce Pink Floyd, Lou Reed, Kiss, Peter Gabriel and a host of other major artists; Alice embarked on a decades-long solo career and earlier this year reunited with original bandmates Michael Bruce, Neal Smith and Dennis Dunaway for the album The Revenge of Alice Cooper, produced by…Bob Ezrin.

The part about Ezrin learning production on Warner Bros' dime while the band was playing like their lives depended on it is wild. I've always thought the best producers are the ones who can hear whats buried under all the noise, and taking an 8-minute meander down to 2:38 without losing the soul of it is kinda the whole game. Reminds me of working with bands in small studios where everyones scrappy and desparate, that energy can actually lead to better decisions than having unlimited time and budget.

The father of the twins next door had a real stereo, the best one in the neighborhood.

Dual turntable, a Kenwood amp and Dynaco speakers.

We were NOT allowed to use it.

But we used it …oh yes…..every day after school ( with a lookout for their dad’s car) to play air guitar and sing every word to every track on Killer with the stereo turned up very very loud.

“I’m a picture of… ugly stor-ies

I’m a killer and… I’m a clown.”